It is high time to reconsider assessment practices in higher education. It probably surprised no one that, as Doug Lederman reported last week, the national effort invested in measuring student learning (a.k.a. learning outcomes assessment) produced little insight into what and how our students are learning. One can only hope that what comes out of accreditors “asking hard questions about assessment” is a more humble approach to educational assessment and a better appreciation for the nature of the learning process itself. Perhaps, we might even stop asking how learning can be measured and instead start thinking about how to represent it in a way that captures some of its complexities, nuances, and messiness!

I am hardly an assessment advocate but I care about education and I have been thinking a lot about what assessment does to students and their learning. This semester, I took a deep dive into research on assessment and learning in preparation for my talk on student self-assessment in our “What’s New in Research on Teaching and Learning” series in March. What I found reaffirmed my belief in the urgent need to revise assessment practices in educational settings not only for educational but also for moral reasons.

Scholars studying student self- and peer assessment have advocated for a better approach to educational assessment for decades. [1] In fact, self-assessment emerges in this research as a counter-discourse to assessment theories that sacrifice student learning in the interest of measurement. This tension is in part because assessment is more concerned with performance as evidence of how much students have learned as a result of instruction rather than with learning itself. It also has a lot to do with psychometric theories of measurement that underlie assessment and that privilege the quantifiable aspects of learning. [2]

To me, the most interesting paradox exposed by the scholarship on self-assessment is that while in social constructivist theories of learning students are at the center of the learning process as autonomous, engaged, responsible partners, they are largely excluded from assessment as active participants. David Boud and Nancy Falchikov (2006) capture this paradox well:

Students have been the subjects of assessment: they are required to undertake tests, they are given feedback on matters that teachers judge important. They are recipients of the actions of others, not active agents in the assessment process. Such conceptions of assessment are inappropriate for long-term learning and they also limit current learning.

As a student-centered approach to assessment, student self-assessment promises to correct this misalignment between assessment and learning. In self-assessment, students can be involved in reflecting on standards of quality in a discipline and developing criteria for evaluating their work. They also learn to apply criteria to their own work and that of their peers, and judge how well their work reflects those standards. Engaging students in the assessment process in this way deepens their engagement with course content and strengthens their metacognitive abilities as self-assessment often involves reflective activities that encourage students to think about and adjust their approaches to learning.

There is ample evidence that suggests a positive impact of self-assessment on student learning. It can improve performance, strengthen motivation and self-regulation, improve feedback literacy, promote the development of evaluative judgment, and foster reflection and life-long learning. [3] Importantly, engaging students in the assessment process in this way can help us make assessment a more meaningful, transparent, and collaborative learning experience.

This is an educational rationale for revising assessment practices towards more innovative approaches like self-assessment. Is there a moral argument to be made as well?

There is, if we consider the emotional aspects of the learning environment. Academic settings can provoke a variety of emotional responses in our students and those emotions in turn determine how well (or not) students are learning. If you’d like to learn more about the relationship between emotions and learning, I recommend the wonderfully lucid and engaging chapter on emotion in Josh Eyler’s new book.

In the realm of assessment, however, student emotions have not been widely studied (with the exception of test anxiety, that is). This is unfortunate because, as Falchikov and Boud show in a different piece, assessment has serious and typically negative emotional consequences for our students. In order to understand this impact, they surveyed a small group of adult education students about their experiences of assessment and what they found is as suggestive as it is depressing. Most surveyed students said that assessments made them feel “nervous and unsure,” “useless and worthless,” “being treated as a child,” “nervous and lacking self-belief,” “on the verge of tears,” full of “disdain and distrust” towards exams, “inadequate.”

We need more research to better understand the emotional aspects of assessment, but I suspect that additional studies would confirm Falchikov and Boud’s tentative conclusions (and our intuitive understanding, for that matter): assessment is a nerve-wracking, perhaps even traumatizing, experience with long-lasting consequences for students’ sense of self-worth and self-image. Because it is difficult (and sometimes impossible) to separate oneself from the work submitted for evaluation, assessment can often feel like a judgment about who we are. “Assessment appeared to be intimately connected to identity,” Falchikov and Boud conclude, “Experiences were taken personally; they were not shrugged off but became part of how these people saw themselves as learners and subsequently as teachers.”

Perhaps anxiety is inherent in any learning situation; some degree of anxiety might be even productive for learning. But assessment practices that jeopardize our students’ mental health and well-being are morally wrong and indefensible.

Can self-assessment mitigate some of the negative emotional consequences of assessment? Perhaps. Without a doubt, self-assessment can be a confusing, frustrating, or pointless activity for students. I am also not convinced that self-assessment is by definition empowering. As an instrument of assessment, self-assessment is entangled with mechanisms of control, surveillance, and discipline, and it can paradoxically extend the reach of the assessment regime.

But assessment is an inseparable part of educational settings and I believe that involving students in this process in meaningful ways can make a difference in how they experience it. Self-assessment has a significant positive impact on students’ self-efficacy, meaning that it can increase their confidence in their ability to accomplish the assigned task, modulate negative emotions like anxiety, self-doubt, and fear of failure, and boost their sense of autonomy and ownership of learning (Panadero et al. 2017).

Those experiences of self-assessment that are positive offer further evidence that the effort we put into redesigning our assessment practices is worthwhile. Here’s a handful of comments from students that I have found especially inspiring:

-

“It made the student feel part of the system rather than a machine that chews out essays and is stressed for weeks waiting for results.” (Mowl and Pain 1995)

-

“Self-assessment … just eases your mind about doing your papers and stuff, it doesn’t make you so anxious and you can actually work ahead a little bit.” (Andrade & Du 2007)

-

“It helps you focus, it helps you get to where you need to be, it helps you learn material” (Andrade & Du 2007)

-

“In my thinking it was more about ‘what have I learned from the whole process, what have I learned? What have I learned by reflecting on what I am doing. What was I aiming to do?’ In the process of doing the assignment, you’re learning on the way, so it changes the way you think about the assignment at the beginning.” (Bourke 2018)

-

“[Commenting on my own work was useful] because you can reflect and see how it could be made better as well as being proud of the good things.” (Orsmond et al. 2002)

Assessment in education is not a neutral practice. As instructors, we often experience assessment of student learning as an administrative nuisance. But for our students, assessment is a formative educational experience that can be either nurturing or damaging. Student self-assessment is hardly a panaceum for all the ills that plague assessment in higher education. But I think it can point us toward a better practice. Perhaps assessment that supports students’ development, and that helps them maintain a sense of ownership, agency, and self-esteem is possible after all?

How to engage students in self-assessment

How you implement self-assessment will depend on various factors specific to your teaching context: the assignments you use, the level of your students, their previous experience with self-assessment, your grading and assessment practices.

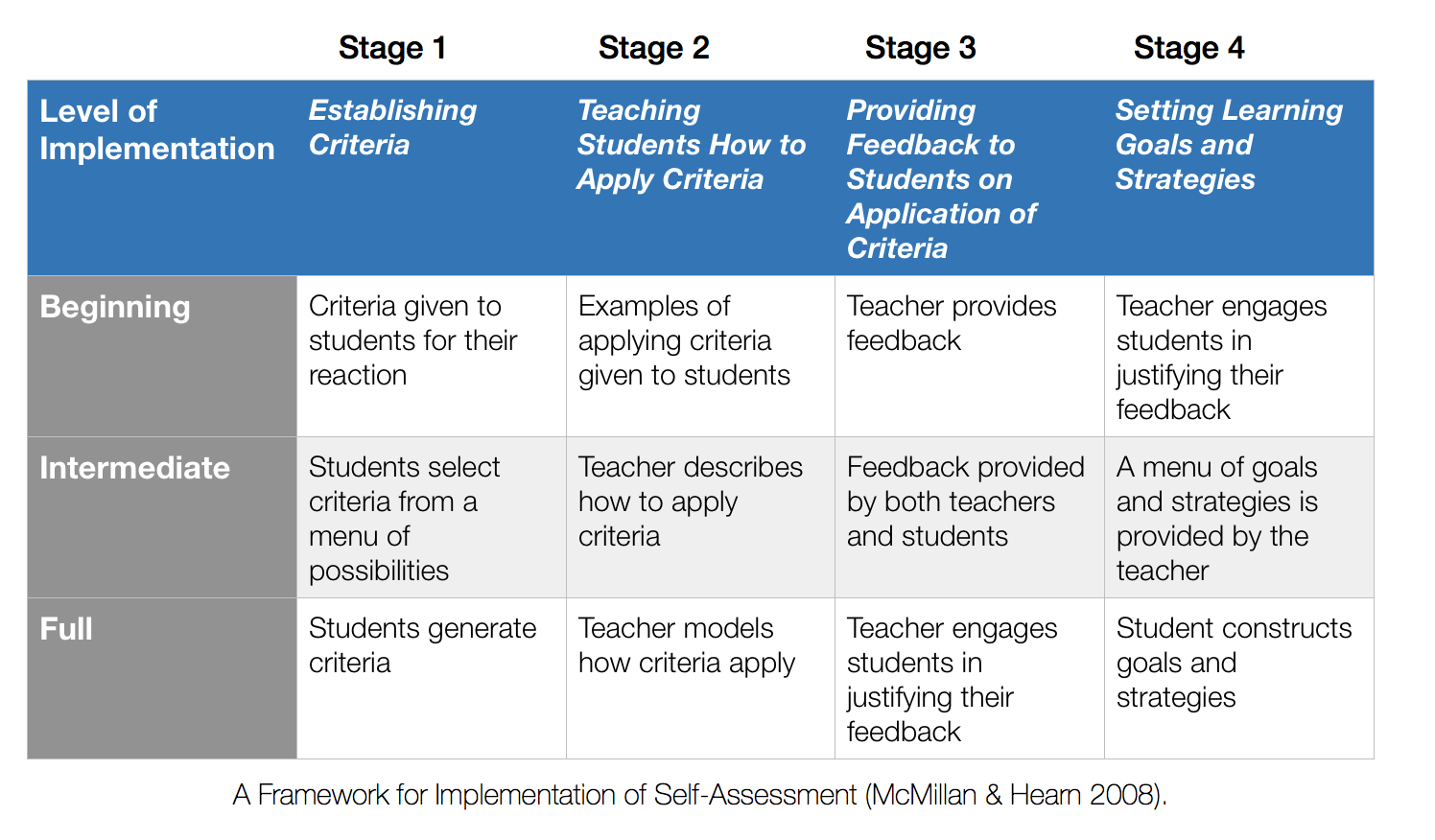

The following framework (McMillan & Hearn 2008) is a good start for thinking about how student self-assessment might fit in your course. It provides general guidelines for implementing self-assessment based on students’ experience with the process.

Prompts to facilitate self-assessment can be wrapped around any assignment. They provide students with the opportunity to reflect on their work, identify its strengths and weaknesses, and consider strategies for improvement. The following questions can help you engage students in self-assessment (Race 2001):

-

What do you think is a fair grade for the work you have handed in? Why?

-

What did you do best in this task?

-

What did you do least well in this task?

-

What did you find was the hardest part?

-

What was the most important thing you learned in doing this task?

-

If you had more time to complete the task, would you change anything? What would you change and why?

***

[1] See for example Boud (1995), Taras (2002), Falchikov (2004), Rust et al. (2005).

[2] If you’d like to follow this debate more closely, I recommend the 2017 issue of the journal Assessment in Education dedicated to assessment and learning.

[3] See Sadler (1998), McMillan & Hearn (2008), Andrade & Valtcheva (2009), Brown & Harris (2013), Panadero et al. (2017), Tai et al. (2018).

Posted on April 24, 2019 by Ania Kowalik